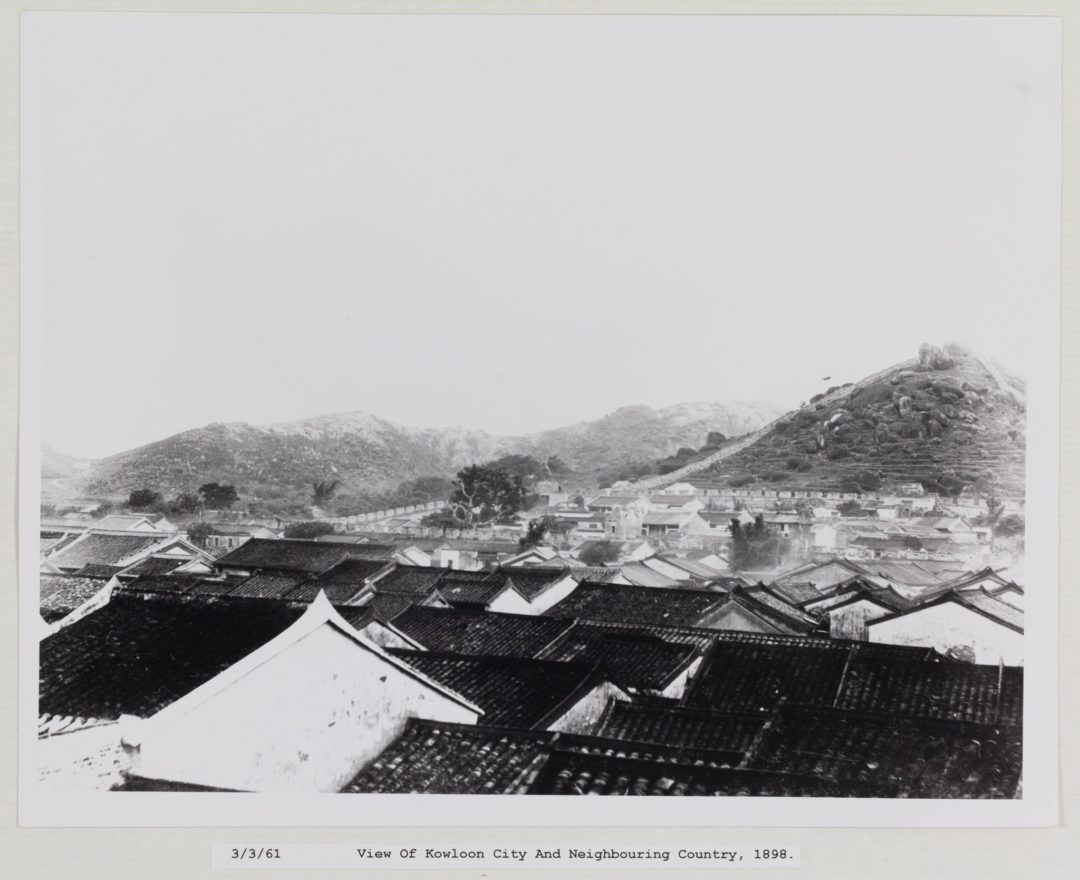

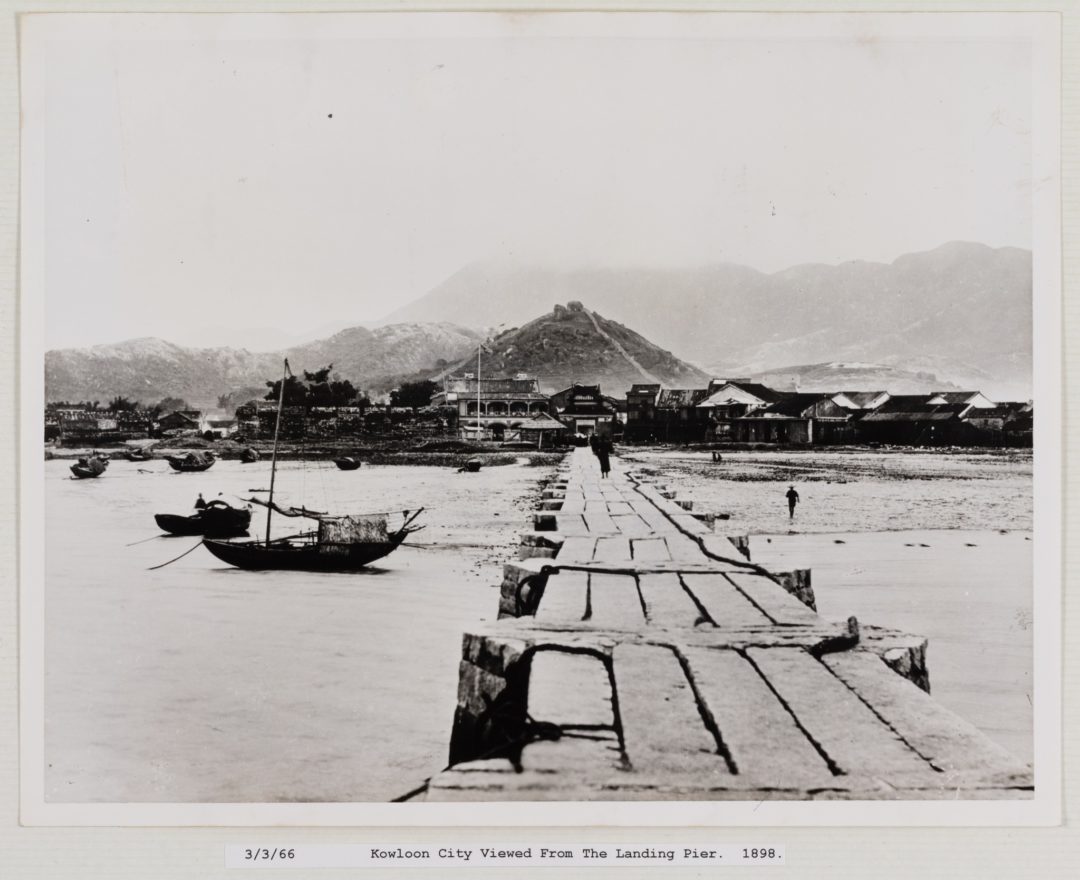

When Qing China signed the lease with the United Kingdom, it retained its jurisdiction over Kowloon Walled City on purpose. Both sides respected the provision in principle. However, during the Japanese Occupation, Japan treated Hong Kong merely as a part of the “occupied territories” and ignored the special status of the walled city. It even destroyed the city’s wall and used the stone for the extension of Kai Tak Airport. The demolition blurred the Sino-British border, laying the ground for future conflicts. The Kowloon City Incident in 1948 was an example.

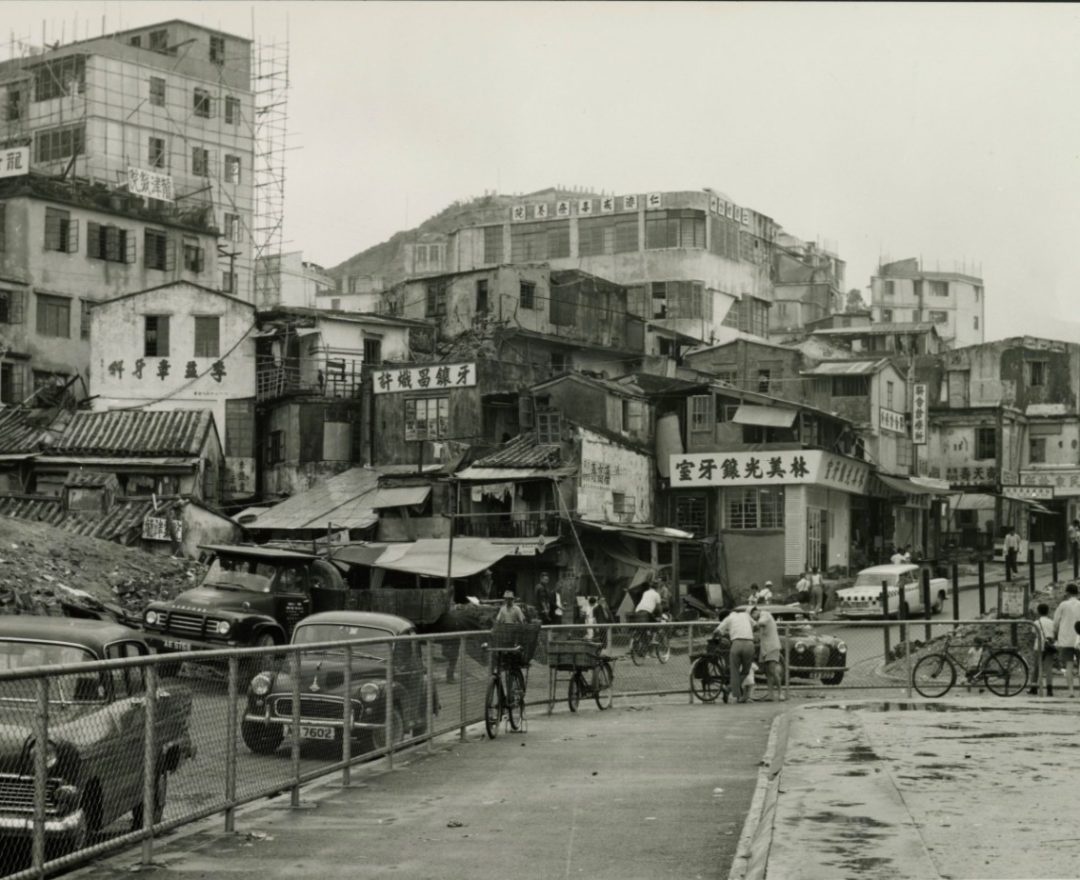

Taking advantage of the disappeared wall, the British colonial government started to exercise jurisdiction in Kowloon Walled City. In November 1947, it applied to the court for an enforcement order to demolish the newly built huts in the city and squatters had to move out within two weeks. In January 1948, it executed the clearance forcibly. More than 70 houses were demolished, many of which were brick houses with a long history. Despite the strong and prompt clearance claiming to be an action against unauthorised constructions, some pointed out that the real purpose was an attempt to exercise sovereignty by the colonial government. The angered residents attacked the bailiff with bricks and the authorities opened fire in return, causing six casualties and two arrests. The incident sparked outrage and protests across the country. Worrying the groundswell could possibly lead to a governance crisis, the colonial government stopped the clearance eventually.

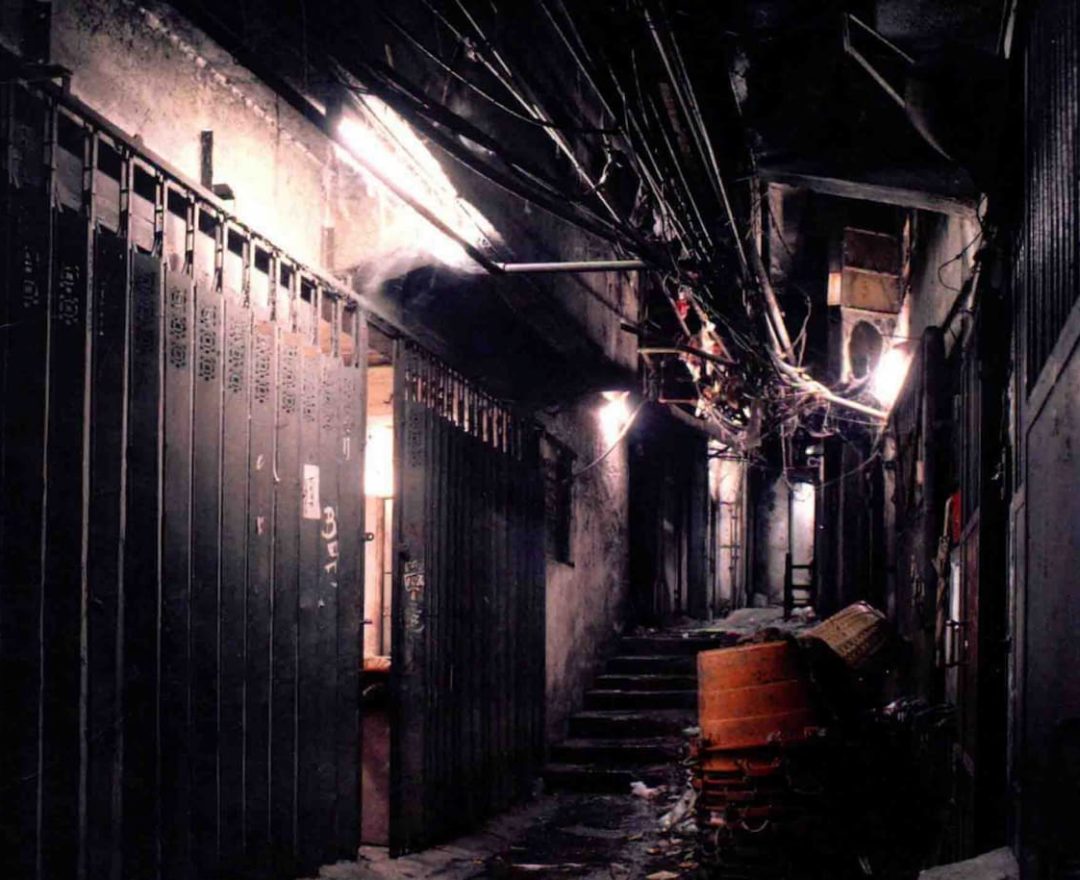

After the Kowloon City Incident, China and the United Kingdom held different views regarding the issue of liability, but to avoid any diplomatic turmoil, they reached a mutual agreement to adopt a “hands-off” policy in the city. The loophole gave rise to squatters and crime. Refugees from China poured in and illegal businesses such as gambling halls, tobacco halls, drug production and trafficking, striptease, thrived. Kowloon Walled City had become a real sin city in the following decades.